A while ago I had a talk with a musician friend of mine. He told me that he had gone to see a modern classical concert. He said that it was an awful cacophony, and asked, “What happened to the art of communication?” I thought that was a very good question, one I have often wondered about myself.

I saw a documentary on television about the phenomenon of genius; in it they said that it was a western concept that someone might be so smart that they could not be understood. Sometimes when an artist fails to communicate with her/her audience, the audience is blamed for not understanding. This is an easy out. It’s too convenient to put all the onus for communication on the listener. I have never been sure where the skill lies in confusing one’s audience. Any five-year-old can be unclear.

Unfortunately, storytellers who communicate clearly are often considered juvenile or pedestrian, such as Hitchcock and Spielberg. When Hitchcock was making films the intelligentsia treated him much the way Spielberg is treated now. His films were seen simply as “crowd-pleasers.” Yet both put so much attention on communicating with their audiences that their very names have become synonymous with film itself.

When I talk to people about communication in art, they often say that they don’t want to be handed everything – they want to figure things out for themselves. Artists who think this way often create confusing art. This is a common trait of intellectuals. The smarter people are, the more they like art that is obscure and difficult to understand.

Yet the smarter someone is the easier they are to fool. Magic, for instance, depends on the viewer’s ability to put together pieces of information and drawing the most logical conclusion. If a magician takes a coin and transfers it from one hand to another, and then the coin is made to disappear, chances are the coin never left the first hand.

But because by the time we are adults we have all seen objects pass from one hand to another countless times, we assume it has happened. I call this gap closing, and smart people are really good at it. A professional magician friend of mine confirmed my observation that scientists and skeptics are the easiest to fool.

Gap closing also happens when someone tells a joke. A joke is just a story with a part missing. That missing piece is supplied by the listener; when they make the connection they laugh. In fact, kids will often exclaim, “I get it!” They have pieced the clues together and closed the gap. With a well-constructed joke we all close the same gap – everyone draws the same conclusion.

If the gap is too close, as in the case of a pun, people often don’t think much of it. The further the gap, the funnier the joke. But there is a limit. Everyone knows if you have to explain it isn’t funny. It often means that the gap is too great and that most people can’t close it. Or that people are drawing different conclusions trying to close it.

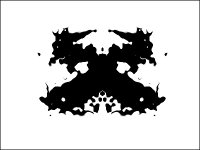

I wish people held “art” the same high standards they hold jokes to – if you have to explain it, it isn’t working. Smart people will often fill in the gap with something that seems to make sense, but if you ask these gap closers what they “got” they will all say something different. I call this “inkblot art,” or when I’m talking about film, “inkblot cinema.”

With inkblot cinema people see what they want to see. They like what they see because they made it up themselves. But often they have done to themselves what the magician does; they have fooled themselves into seeing something that is not there. Like a skillful magician or comedian, a good storyteller can use this gap closing to his/her advantage. Hitchcock called it pure cinema. He let the audience close gaps all the time.

In Frenzy Hitchcock shows us a brutal murder. Later in the film, he shows the killer disappear into an apartment with young woman. As the killer closes the door, he uses the exact words he used just before he committed the earlier murder. Then he keeps the viewer outside the door to imagine what is happening on the other side. Everyone is closing the gap like crazy, but we are all closing the same one. We all know a brutal murder is taking place on the other side of the door.

Billy Wilder said, “Let the audience add up two plus two. They’ll love you forever.” Just make sure you have communicated well enough that the audience knows the answer is four. Don’t hide behind your inability to be clear or rely on the ability of your audience to make up something where there was nothing.

Bring back the art of communication.

(What I call gap closing Scott McCloud calls closure. Same observation. He has a great explanation of it in his book Understanding Comics. If you don’t have it – get it.)

5 comments:

Great post! Besides people wanting their films/art to be intellectual and hard-to-get, there's a resistance sometimes to 'pandering' or playing down to the audience: the final film has got to be exactly what you envisioned originally, and if they don't get it, nuts to them.

Which is really kind of like going up on stage and wanking off...

Anyway, I think it's also true that storytelling is MORE difficult than being obscure. Telling a complicated story so that everyone can follow it is like a juggling act, with knives on fire!

Thanks, Emma. I'm glad you keep reading.

The very definition of art lets the viewer interpret, to read into. That is it's function in society. Both good and bad art live on the same plane of validity, and that's well and good.

But telling a story, communicating, well that may be an artform, but rarely is it considered art. Because it can't be up for inrepretation and man is that hard!! Although if you can make the audience feel like they are the ones discovering it outta the blue, your gold!

Me being and illustrator, the best illustrations (telling a story in one picture) that I know of, are "the gap". It draws the viewer in to wonder what led up to this and what is gonna happen because of this, and man is that hard! It's easier to paint the color blue or a nekkid lady and leave it up for interpretation. But it's not telling a story it's just leaving it up for the viewer. Tell a story, the audience will love you for it indeed!!

as Ive said "The key to language is understanding. The definition of communication is a mutual comprehension. Its chic these days to leave out the predicate, to be vague when speaking, to present jumbled images and sentences, to not be precise and comprehensive. We tend to see someone like David Lynch, who has no cohesion in his movies, as being brilliant, because we do not understand what is going on, we assume He must be smarter than we are, that he gets it.

David Lynch in some way, is kind of like God in that case."

Yeah, that's exactly right.

Post a Comment