King Kong was one of my favorite movies. Until recently.

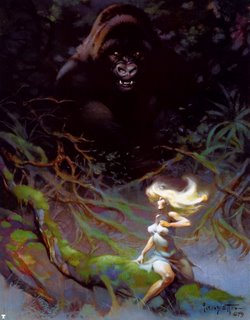

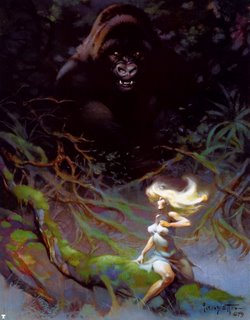

While flipping through a book on the making of the 1933 film, I saw a pre-production drawing: a white woman cowers in bed as a big, black gorilla reaches for her through the bedroom window. I wondered why the filmmakers decided that King Kong should find the woman in her bedroom. Something about this image disturbed me, so I decided to watch the film again.

King Kong is about a white man, Carl Denham, who sails to an island in search of something he can bring back to America that will bring him wealth. Along with the ship’s crew, Denham brings a young woman, Ann. He finds that the jungle island is populated only by black people. Denham and his men come across the black natives and witness a strange ceremony: some of the natives wear gorilla arms as they dance around a native girl. When the white men ask what’s going on, they are told that the girl is the bride of Kong. Spotting the white woman, the Chief asks the white men to trade the “Golden Woman” for six of his. He wants her for the bride of Kong. The white men refuse to hand over Ann, so the natives kidnap the woman and offer her up to Kong as a bride.

Kong, a giant gorilla, carries Ann to a mountain ledge, and after she has fainted, he starts to remove her clothing.

The white men manage to rescue Ann from Kong, and soon after, they capture Kong himself. Denham says that he intends to take Kong back to civilization to make himself and the crew millionaires.

Denham and his crew take Kong back to “civilization,” as Denham calls it. There, Kong is chained and displayed on a steel platform on a stage. Kong breaks free from the manacles biding his arms, neck and waist. He then goes on a murderous search through the city looking for Ann. By climbing a building and peeping into windows, Kong finds Ann in her bedroom with her fiancé. The woman faints across her bed. Kong reaches through the window, pulls Ann’s bed toward him, and carries her away.

As the ape carries Ann to the top of a skyscraper, she struggles to break free of Kong’s grip. Biplanes buzz Kong and he sets Ann down on the ledge to do battle with them. The pilots take this as their cue and riddle Kong with bullets. Kong falls to his death.

I submit to you that the character of

King Kong is not just a movie monster, but a metaphor.

Look again at the story. When Carl Denham finds the black inhabitants of “Skull Island,” they are wearing arm extensions to make them appear ape-like. The effect is an eerie blend of man and animal. The natives are also preparing a girl to be the “Bride of Kong.” A strange thing for an animal to want a human mate, don’t you think?

The black Chief offers the white men six black women for the “Golden Woman.” One white woman is equal to six black women, even to black men. What does this imply about the worth of black women?

The white men refuse this offer and the black men kidnap the white woman. This seems to play on a major white racist fear. Does the term “stealing our women” sound familiar? This idea is strengthened when you realize that this theft takes place right after Ann and her white love interest share their first kiss. Now that Ann “belongs” to a white man, she can be stolen from him.

Ann is tied to an altar, which seems to exist expressly for offering Kong his women. We are given the impression that if Kong’s ravenous sexual appetite is not appeased, there will be hell to pay.

Kong takes his white “bride” to his cliff-side home, and after she faints, the “ape” begins to remove her clothes. This violation can be seen as rape.

The white men rescue Ann from Kong, and soon afterward capture Kong himself. Denham says that he’s taking Kong back to “civilization” to make himself rich. The act of taking Kong out of the jungle and exploiting him for money mirrors the slave trade.

“No chains will hold that!” says the ship’s captain. This prophetic statement echoes the idea of black anger at being held in bondage. He is saying that once you put them in chains, you’d better make damn sure that’s where they stay.

“We’ll give him more that chains,” declares Denham. “He’s always been king of his world, but we’ll teach him fear.” Denham calls Kong a king, which raises a few questions. We see no other apes on the island, so are we to assume that Kong is king over apes, or a king over the black natives? Is the film saying that black people are apes or that Kong is human?

Kong is taken by ship to America, put in chains, displayed in a theater. On the theater’s stage is a large platform similar to an auction block, upon which the shackled Kong stands for the theater audience’s inspection. Why was Kong put on the block? Aren’t all stages designed for easy viewing? Isn’t Kong large enough for the spectators to see already?

There are no black people that I could find in Denham’s “civilization.” Kong has gone from and all-black world to and all-white world one. Again, and echo of the slave trade.

Kong breaks his chains of bondage, and, once free, immediately goes on a murderous rampage through the city, looking for his white woman. Kong’s sexual appetite must be satisfied. He finds Ann in her bedroom with her fiancé. Seeing Kong, she faints across her bed. Kong reaches through the window, pulls Ann’s bed to him, and takes her. This is a playback of the earlier scenes where the black men took the white woman from her man, as well as the mountaintop “rape scene.”

Kong finds the city’s version of a mountain-a skyscraper-and carries Ann to its top, implying that the ape’s jungle ways are out of place in the city. The woman struggles to pry herself free of Kong’s big black hand, even though she is hanging hundreds of feet in the air, and falling would mean certain death. Death is preferable to being with a black beast.

After a battle with machine gun-equipped airplanes, Kong plummets to his death.

Denham says: “It wasn’t the airplanes. It was beauty killed the beast.”

Denham takes no responsibility for the murder of Kong. It was Kong’s own animal urges that killed him. The pilots only did what was necessary to protect the white woman from the

black animal.

The references to Beauty and the Beast are made several times throughout the film. In that story, the beast was not an animal, but a man who only looks like a beast. Is this the film’s point; that Kong is really a man who looks and acts like a beast?

In reviewing the movie, what I saw confirmed my fears. What disturbs me about the film isn’t that the people feared King Kong, but why they feared him. Understanding why has brought me to a conclusion that not only images are burned into celluloid, but attitudes and beliefs as well.

No, King Kong is not just a movie monster, but a metaphor for black male sexual aggression as seen by America’s white racists.

Why is it important to talk about a film released nearly 70 years ago?

Because I believe we still carry these images with us and that they affect us daily.

A few years ago, TV meteorologist Michelle Leigh at WDIV in Detroit proved my point. At the end of the newscast was a feature story on eligible bachelors. A woman in the video clip said that she was looking for a man with “chocolate skin.” This story was followed by a news clip about a 415-pound gorilla. When the camera returned to the anchor desk, Leigh, who is white, pointed to a monitor and asked her co-anchors, who are both black, “Does that qualify as chocolate skin?” referring to the gorilla.

I still like watching King Kong. There is still a little boy inside of me that enjoys losing himself in the fantasy of cinema. As a black man, however, I live with the reality that to many Americans, I am Kong-an angry animal in pursuit of the white woman, and is therefore better off locked up or dead.

The Peter Jackson Remake of King Kong Opens Dec 15th.

http://www.google.com/gwt/x?wsc=yq&wsi=6776b999433a9b55&source=reader&u=http%3A%2F%2Fnews.stanford.edu/pr/2008/pr-eber-021308.html&ei=nLetTc_1Dpm4wQWK84kV&ct=pg1&whp=30